Misinformation spread fear and delayed a timely response.

During the recent outbreak of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) in South Korea, the nation’s government was heavily criticized for its response. In a nation still smarting from the inefficient response to the Sewol ferry disaster about a year ago, mismanagement of the outbreak by hospitals and by the Ministry of Health and Welfare frustrated citizens, contradicting articles that state “South Korea is handling this well.”

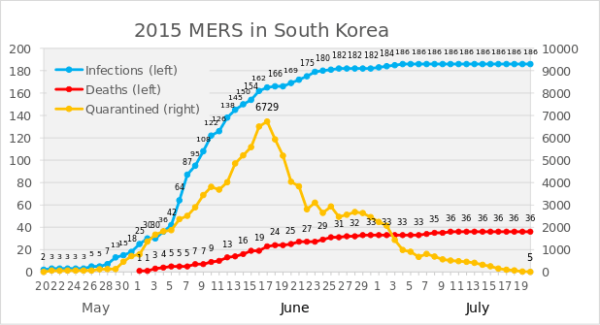

The withholding of basic information, such as the names of the hospitals suspected of carrying MERS patients, and only exposé of MERS deaths through news outlets escalated anxiety. Not knowing the scope of the threat, entities outside of the government and hospitals reacted on a large scale, from closing schools–1,300 schools initially closed–to selling out of masks.

Image Source: Chung Sung-Jun.

After 14 days of the outbreak, the nation was shocked to find out that the epicenter of the outbreak was none other than Samsung Medical Center (SMC). Often regarded as the best hospital in the nation, SMC had accumulated a trustworthy reputation, yet it was pressured to issue a public apology and temporarily closed its doors. More than half of the total MERS cases were traced to SMC.

MERS migrated to Korea and then spread mainly as a hospital-acquired infection (HAI).

After visiting Saudi Arabia–known as the country with the most MERS cases–and other countries in the Middle East, patient zero began displaying symptoms of the disease. In seeking treatment, he went “hospital shopping“, visiting four different hospitals. One of the hospitals that treated patient zero placed a doctor on “self-quarantine”, but the hospital staff did not retain the doctor in a separate isolation room, letting the doctor travel abroad. Countries such as Vietnam expressed concerns over contracting the disease through Korean visitors.

The nosocomial disease, or hospital-acquired infection (HAI), spread in three out of the four hospitals. Most patients contracted the disease by being treated in close proximity with subsequently infected patients.

Image Source: Chung Sung-Jun.

Administrations in Indiana and Saudi Arabia have responded to MERS.

Not all hospitals have handled MERS epidemics this way, however. South Korea could have modeled their response after Indiana. In 2014, a non-profit Indiana hospital identified symptoms of MERS in a visiting patient who had returned from acting as a healthcare provider in Saudi Arabia. Medical staff placed the patient in a private triage room. They then identified those who had been in close proximity with the patient by tracking sign-ins of personnel, and placed 50 potentially infected people on quarantine.

Saudi Arabia fired their Deputy Health Minister after what they judged to be an inadequate, untimely response to the MERS outbreak in 2012. Higher officials sacked the Deputy Health Minister Ziad Memish for not being open to outside help from specialized laboratories, and inadequate infection control procedures. The death toll amounted to 282 by that time. The recent resurgence in cases of MERS has alarmed some people, as the upcoming annual hajj migration will draw more people to Saudi Arabia.

Similarly, the lack of transparency and lax infection control has been criticized in Korea. The South Korean government must implement longer-lasting changes that will facilitate a faster response next time.