Cancer is a terrifying disease that eventually overpowers the body’s immune defense to fuel its own erratic growth. There are many different types of cancer based on the area of the body it originates from, but the deviancy of cancer is attributed to its uncanny ability to metastasize, or spread to other parts of the body, by dislodging a part of itself and dropping the cells into the bloodstream for distribution. Once the dislodged chunk of cancer cells finds itself in a new environment, it starts to form another tumor colony. If enough tumors begin forming, the person may die because the body may not be able to support the tumor growth, and subsequent organ failures and the blockage of blood vessels prevent transportation of nutrients to important areas of the body. Although cancer is still being extensively studied, we know that during metastasis, breast cancer tends to spread to the bones; however, we do not know the mechanism behind it.

Image Source: Lester Lefkowitz

After years of cancer research, scientists have finally cracked how breast cancer spreads to the bone. Published in Nature, scientists found that when breast cancer metastasizes to the bone, it increases the production of lysyl oxidase (LOX), creating bone lesions. This enzyme acts as a regulator of osteoclastogenesis, the generation of new bone, by disrupting normal bone homeostasis and forming holes in the bone. These holes serve as a platform for breast cancer cells to take root and grow. In mice studies, there is already an identified drug called bisphosphonates, usually used to treat osteoporosis (bone loss), that has a significant effect in preventing bone lesions caused by the lysyl oxidase. Through such a treatment, the chances of cancer metastasizing to the bones decreases, thus improving the odds of cancer survival.

For now, it is unclear whether treatment with bisphosphonates for humans will successfully prevent breast cancer from invading the bones, but mice studies certainly are promising. If this is true, then the development of similar drugs to bisphosphonates may increase cancer patients’ lifespan and be a viable treatment option for breast cancer.

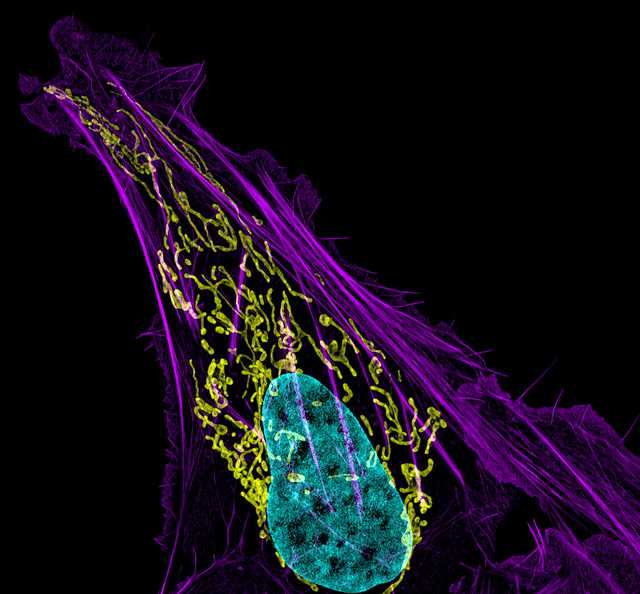

Feature Image Source: Bone cancer cell (nucleus in light blue) by ZEISS Microscopy