Genome editing used to be the stuff of sci-fi movies, with movies like Gattaca depicting a world where it was easy to manipulate genes in order to create “perfect” humans. With zinc-finger nucleases and transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs), genome editing has been around since 1996. In short, these techniques combine a protein that binds to a specific area of DNA with an enzyme that cleaves DNA to create a structure that will cut at a desired sequence. This allows a lot of changes to be made to DNA, either by editing the sequence itself, deleting base pairs, or adding new base pairs at the cuts. The cell will then repair the damage.

This is easier said than done, and until 2012, it was pretty difficult to use. The advent of the editing tool CRISPR/Cas9 has made it much easier. This system takes advantage of a form of bacterial immunity against invading viruses, where the bacteria uses this system to recognize invading viral DNA. It’s a pretty complicated process when you extend it to editing human genes, but the bottom line is that it can be used to turn on genes, turn off genes, and edit them. It has already been done in animals.

Okay, so this sounds pretty useful! Some diseases like sickle cell anemia are caused by very small mutations in genes, and this technology gives us the ability to fix them. But there are a couple issues.

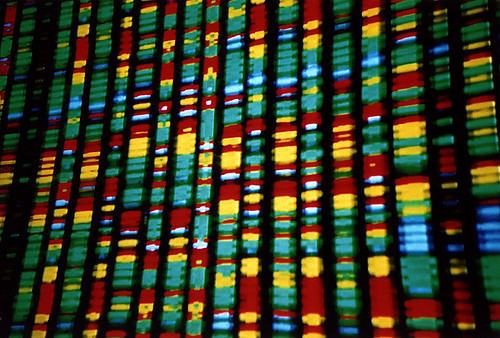

Image Source: Pgiam

It’s possible that something like Gattaca could occur: people trying to manufacture the perfect child by manipulating their genes. Scientists are thinking of using it to edit germline DNA–the DNA of eggs and sperm, where the information in all of your cells arises–which means that the edits would be passed on to future generations. Researchers have expressed concerns about these inheritable changes because not much is known about what could happen. What if the germline DNA modification has a previously unknown harmful effect? Also, the enzymes in CRISPR aren’t perfect and can sometimes cut in other places in the genome. These are known as off-target effects.

Scientists suggest that it might be best not to proceed too hastily with this powerful tool. Jennifer Doudna, the inventor of CRISPR, is one of the leading scientists suggesting a moratorium on human germline genome editing until all risks are assessed. It’s not necessarily looking to stop all future laboratory research with CRISPR–the more research that’s done, the more we’ll understand about this technique. The moratorium would be specifically for germline modifications with clinical applications intended for use in humans.

The ability to edit genes and pass them on to future generations doesn’t necessarily mean that we fully understand everything that could happen when the genes are manipulated. Regardless of whether scientists will be told to stop, discussions and guidelines for human genome engineering are needed.

Feature Image Source: Andy Leppard