Many may have heard horror stories about the V.A. (Veterans’ Affairs). They have ridiculously long wait lines; accusations involving these long wait lines and other bureaucratic issues resulted in a scandal that led the V.A. chief to resign. What might be striking, however, is that these problems are easily preventable. V.A. healthcare is not a money issue. The primary issues lie in technology and awareness.

Mr. Jeremy Ramirez, former service member, now in the Masters of Public Health program at the University of California, Berkeley, elucidated that most returning servicemen and servicewomen become eligible for medical benefits once screened at a Veterans Transition Center, but more awareness is needed for soldiers to seek and access these resources.

What happens to soldiers in Walter Reed National Military Medical Center deemed unfit for service?

In Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, where all critically injured overseas servicemen and servicewomen are processed, soldiers may be deemed too severely injured to return to service. During out-processing, they attend a two-week seminar exposing them to various resources, such as GI Bill benefits and local VTC’s. However, Mr. Ramirez stated, the rate at which information is flung at them is akin to them trying to “drink from a fire hose”. Often these newly minted veterans forget most of the information trying to arrange their other affairs in order, and may take a while to seek help from the V.A., or forget about seeking a VTC altogether.

What happens at a Veterans Transition Center?

The first visit involves registering by filling out paperwork. The veteran often needs to set aside an entire day to wrestle with papers. During this visit, they are also encouraged to meet with a case manager, who could be either a registered nurse or social worker. Sometimes the patient may be assigned to a patient aligned care team, which includes: “A primary care provider, nurse care manager, client associate, and administrative clerk.” Questions such as “Are you in school, are you working, how’s your family life, are you adjusting, are there any services that you’re interested in,” may emerge during this conversation. They also experience a “head-to-toe” screening and a comprehensive review, because the veteran’s health profile must be constructed from scratch.

“If the service member is eligible for job training services or self-help groups, the case manager will educate them on what’s available, and if it’s not available at that medical center then it might be more accessible to the veteran at a satellite clinic closer to the veteran’s residence,” Ramirez stated.

The second stage involves attending many pre-screenings, which need to take place over a series of scheduled meetings, to complete the veteran’s health profile.

Image Source: Scott Olson.

Why the need for such a comprehensive review, if data already exists from when they were on active duty?

The fault lies with two conflicting data systems. A discrepancy in technology basically creates critical delays in post-battlefield care.

Most medical records for those on active duty are saved in Armed Forces Health Longitudinal Technology Application (AHLTA), an electronic medical record system (EMR, also called EHR for electronic health record). Most veteran records, on the other hand, are saved in another EHR, the Veterans Health Information Systems and Technology Architecture (VistA). There is little to no transfer of information about a particular veteran between the two systems. Therefore, records are not transferred with the discharged service members, so a health profile must be re-constructed.

Much more time passes for veterans to secure resources, than if they would with a single, unified EHR.

There is a multi-billion dollar initiative to unify the two EHRs, Ramirez explained. This task is difficult because VistA is probably one of the largest and bulkiest medical record databases, with profiles dating back to veterans who served in the Vietnam War. Much delicacy is required to avoid potentially damaging already stored information while modifying one database.

The V.A. is also pushing to supply soldiers with information chips, as part of their strategic plan to track a soldier’s health record. The hope is that these chips will compact information from AHLTA, and can be given to a case manager or a veterans transitional officer to plug in to VistA.

Yet, there are some problems experienced in the military that are not recorded in AHLTA. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is often not identified in those on active duty because of the stigma against this disorder in military culture.

How prevalent is PTSD in the military, and what is its surrounding culture like?

When asked about the prevalence of the disorder, Ramirez took some time to word his thoughts. As he had provided rapid-fire and articulate answers throughout the interview, his hesitation demonstrated an ingrained difficulty in discussing this topic.

You are currently looking at the face of a former combat medic, serviceman, and proud VA staff member. Source: Christy Kim.

“When someone… when someone is subject to such trauma, it would be an oversight to not expect a large percentage of the population to end up with consequences from this trauma.” He pointed to comorbidities as another source of grievance, because when the PTSD passes undiagnosed, a veteran might self-medicate by abusing substances while not even understanding what they are self-medicating. The hyper-masculinity of military culture, he explained, promotes a certain kind of environment where “weakness” is frowned upon, and in some cases, mentioning a mental disability would prevent promotion within the ranks.

Along that vein, he mentioned that servicewomen often go through a unique set of problems in this hyper-masculine environment. Often case managers need to refer these servicewomen to specialized support groups. Cases of emotional abuse and rape emerge; many servicewomen experience these rape cases as forced incest, because they regard their fellow servicemen as brothers, and get used to keeping quiet for the sake of keeping the “family” peace. The Department of Veterans Affairs uses military sexual trauma (MST) to refer to such cases of sexual assault or sexual harassment the veteran may have experienced in the military.

Re-diagnosing these problems, however, is preferable to not seeking any help at all. Often, veterans need to overcome the stigma portraying needing help as a weakness. There is also a dire need for more awareness because VA and satellite clinics are prepared to help veterans. They are well-staffed and can provide CBT (cognitive behavioral therapy) and other treatments for disorders inflicted by the war.

It is often more difficult to keep track of homeless veterans, Ramirez acknowledges. Attending a clinic and meeting a case manager, he stated, eases the veterans’ transition back into civilian life and informs them of the resources at their disposal. The VA has drastically improved in recent years, and he anticipates that they could aid more servicemen and women if more awareness is spread about their recent changes and initiatives to cut down wait times.

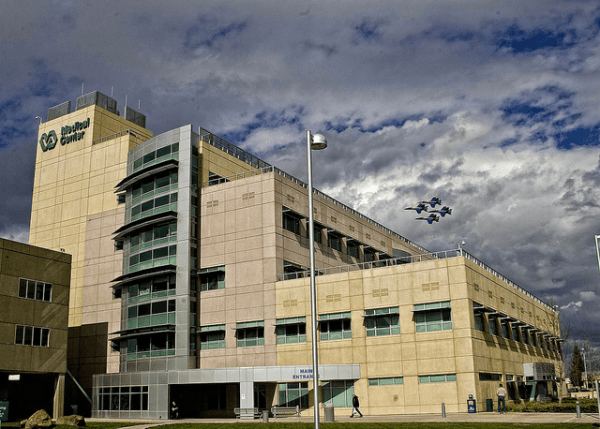

Featured Image: Sacramento VA Medical Center by Veterans Health.