It has long been suspected that children born into wealthier families receive a higher quality of education and perform better on standardized tests than those who are born into poverty because of their access to enrichment resources. A recent study published on March 30, 2015 in Nature Neuroscience suggests that there is a substantial and physical correlation between socioeconomic status and school performance, test scores, and educational opportunities.

A parent’s education, occupation, and income are factors that characterize a child’s socioeconomic status and play an important role in a child’s cognitive development. Cognitive development includes information processing, intelligence, reasoning, language development, and memory. This process begins in the womb and continues throughout adolescence to adulthood. Children who are intelligent have larger brain surface areas that continue to grow as they reach adulthood.

Led by neuroscientists Kimberly Noble from Columbia University Medical Center and Elizabeth Sowell from Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, the study examined 1,099 individuals between the ages of 3 and 20 using MRIs (magnetic resonance imaging). To account for race and genetic ancestry, researchers gave standard cognitive tests to the subjects and took DNA samples. The results were also adjusted for age, sex, and MRI anomalies.

Image Source: Bloomberg

The results showed that children from families making less than $25,000 had up to six percent less cortical surface area than children from families making more than $150,000. Children of parents who had 10-13 years of education (high school) had five percent less surface area than children whose parents had 15-18 years (college). Those from highly educated families tended to have a larger hippocampus, the part of the brain involved with learning and memory. Parental education had a positive linear relationship with a child’s brain surface area, while family income was logarithmically associated with surface area. This means that even small increases in income during the first few years of a child’s life can have a significant impact on cognitive development and adulthood achievements.

The standard cognitive tests showed that cortical surface area had a direct relationship with performance. Those who came from poorer families, thus smaller brain sizes, performed worse compared to other subjects in the study. This was especially true for tests that measured executive function and memory. The results of the study and the relationships drawn between socioeconomic status and cognitive development were the same across all ethnic groups.

The study has yet to find the reason behind these differences in brain size. But it is clear that a change in income and education can impact children of lower socioeconomic status. Childhood poverty must be addressed and antipoverty measures must be taken. Through more nutritious diets, personalized academic care, and other enrichment programs, a child’s brain development can be improved.

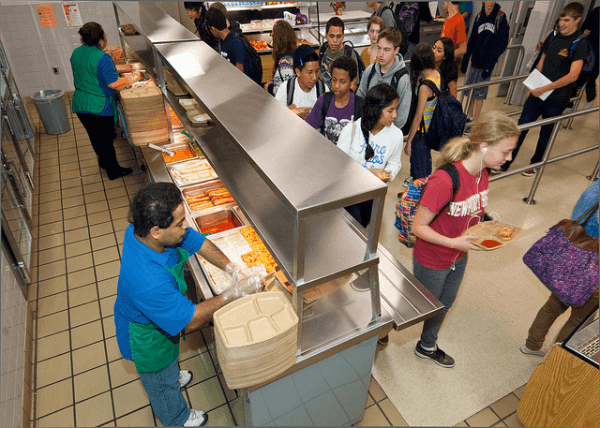

Featured Image Source: U.S. Department of Agriculture.