The common cold is nothing to sneeze at. It leads to 3,000 to 49,000 US deaths a year and may be responsible for five to 20% of American’s sicknesses each year. It also has a broad presence; every child gets infected before their second birthday. Easily spread through coughs and sneezes, the virus will then infect lungs and airways, leading to a heavy cold, bronchiolitis and/or pneumonia.

Recently, in a study published in the journal Nature Communications regarding the prevention of infection, researchers at the Imperial College London in the UK found more evidence that higher numbers of immune cells called memory T cells help fight the common cold. Furthermore, these researchers found that resident memory T cells can perhaps be activated via nasal sprays.

To study how the memory T cells influence the development of the viral infection, the researchers infected 49 volunteers with the virus. They measured and compared tissue samples from the participants before and after infection, looking specifically at the overall number memory T cells. At the end of 10 days, a little more than half the participants had developed an infection.

Image Source: Cultura RM Exclusive/Colin Hawkins

Of these infected participants, those with more active memory T cells before the infection had fewer symptoms and fewer viruses, suggesting that the immune cells help protect humans against the virus. This implies that activating more memory T cells helps humans fight infection. Memory T cells basically raise the alarm for other immune cells to kill invaders once they find the viruses.

Additionally, the researchers concluded by looking at the numbers of immune cells in blood and nasal discharge samples and tissues removed from the subjects’ airways, that immune cells called resident memory T cells located in skin cells near barrier cell areas like the respiratory or gastrointestinal tracts, might help better fight the common cold.

These memory T cells are different from regular memory T cells in two ways: the unexpected location, and the different receptors for receiving antigens on the virus. By delivering a vaccination against the virus through nasal sprays, doctors could potentially reach the resident memory T cells most effectively, preparing the immune cells to fight the virus.

Inspired by the human body’s limited defenses against the virus, the researchers aim to discover how to boost the body’s existing defenses against the virus. With the results of the study, they hope a vaccine—one that might involve vaccinations through the nose rather than needles in arms—will be ready for use within the next few years.

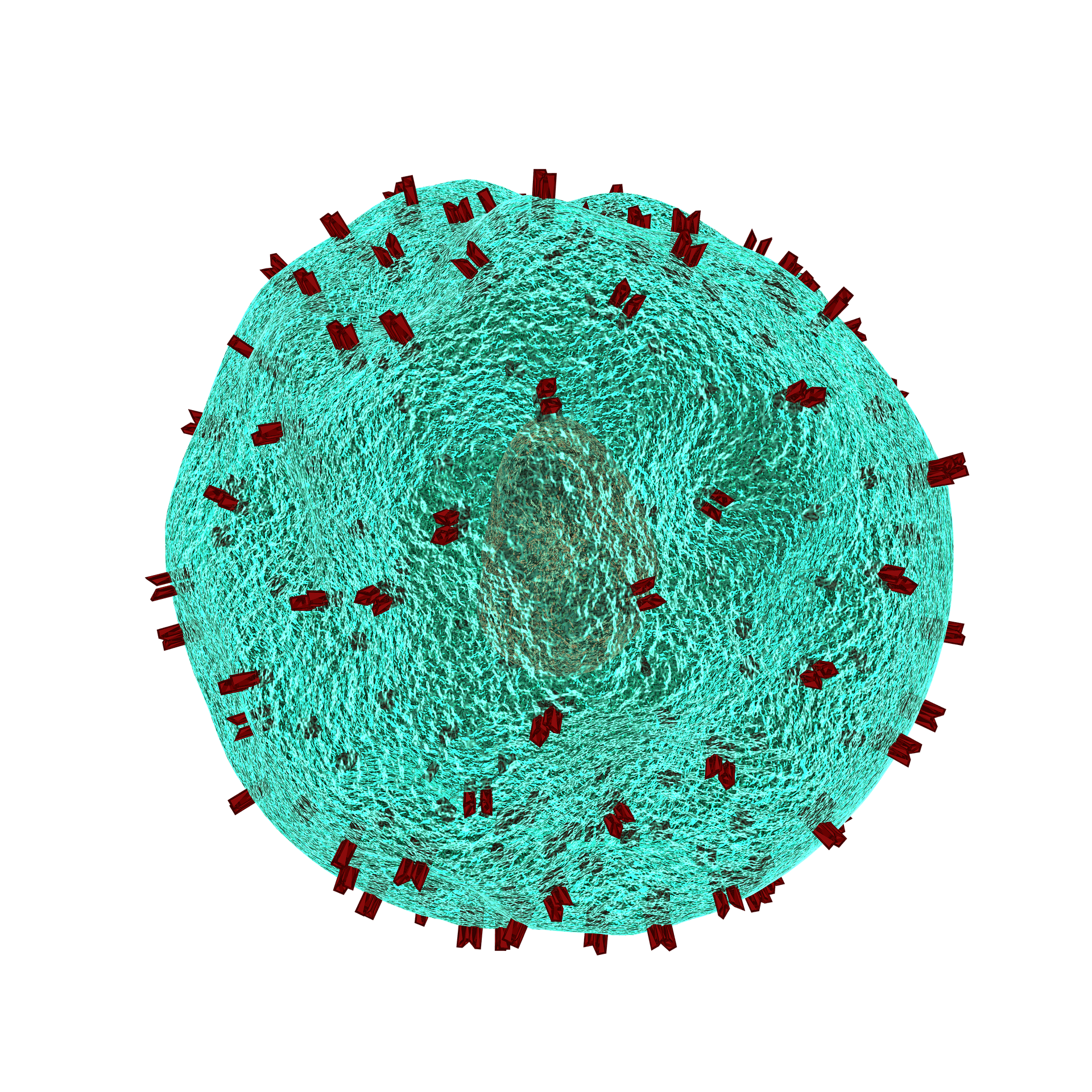

Feature Image Source: Allinonemovie