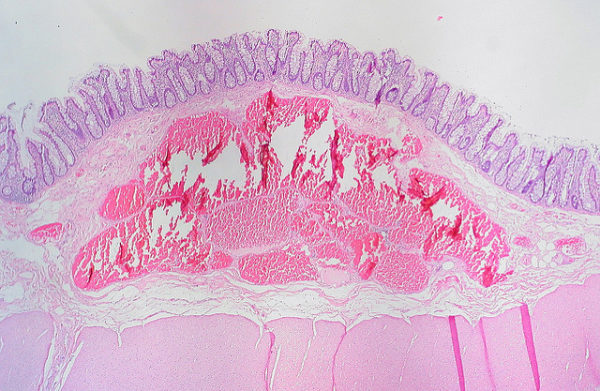

Exciting news spread throughout the biology world this past March: the discovery of a new human organ previously hidden in plain view. Termed by researchers as the “interstitium,” this organ consists of fluid-filled interstitial space supported by a complex network of thick collagen bundles. It is actually one of the largest organs in a human: it lines the gut, muscles, lungs, blood vessels, and other areas, and serves as a barrier between the skin and different tissue types found in the body.

Image Source: Science Photo Library

The findings alter previously well-regarded facts of human anatomy. In the current scientific world, the various types of tissues such as submucosa and dermis that line different organs in the body are thought to be densely packed, barrier-like walls of collagen. However, with this new information, researchers have now argued that these tissues contain fluid-filled interstitial spaces. The presence of fluid is important for bodily function: comparing frozen tissue and standard tissue has indicated that this fluid is compressible and distensible, which would give the fluid shock absorbing properties. This is further supported by the fact that all organs with the detected interstitium structure are known to contain cycles of compression and distension. Another form of data that supports this hypothesis used ultrasonography. Submucosa interstitium under ultrasound appeared heterogenous, usually indicative of fluid tissue. For example, this matches what is seen in the ultrasound of the fluid-filled middle layer of the bile duct.

The fluid nature of this newly found interstitium would lead to much further investigation to discover the exact mechanisms of how the tissue affects organ functions. First off, instead of being a wall-like barrier, the interstitium can potentially serve as a conduit for the transfer of harmful agents such as cancer cells. This is seen through interstitial fluid flow from the submucosal space of the gastrointestinal tract into the lymphatic system, which transports lymph, the bodily fluid that contains white blood cells important in the body’s immune response. Therefore, the new organ could hold the ability to spread cancer throughout the body, but more research would need to be done to reach adequate conclusions. In addition, fluid transport is likely regulated by a process called peristalsis, a series of wave-like muscle contractions. This suggests that the speed of peristalsis could be altered to regulate important cell signaling such as immunological signals, which are important in inflammatory conditions such as scleroderma. Overall, while exciting news, the discovery of the interstitium opens up many doors for scientists to take in the hopes of fully understanding the function and effects of this new organ.

Feature Image Source: Sigmoid Colon, Submucosal Hemangioma by Ed Uthman