How is one individual who experiments with cocaine able to leave the drug alone when another individual who experiments with the same drug develops a drug habit? The answer to this question lies in specific genetic factors that vary from individual to individual, as published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences by a University of Michigan Medical School Team. The scientists conducting the study were able to breed animals selectively. These animals had an inclination for addiction, linked to differences with expression of genes for specific molecules in the part of the brain that is associated with reward and pleasure, the nucleus accumbens (NAc). The dopamine system associated with NAc allows people to respond to pleasant experiences and encourages them to engage in those experiences again. However, if a strong drug, like cocaine, takes over this system, which fuels normal reward and pleasure, the entire goal-driven/motivator system goes awry.

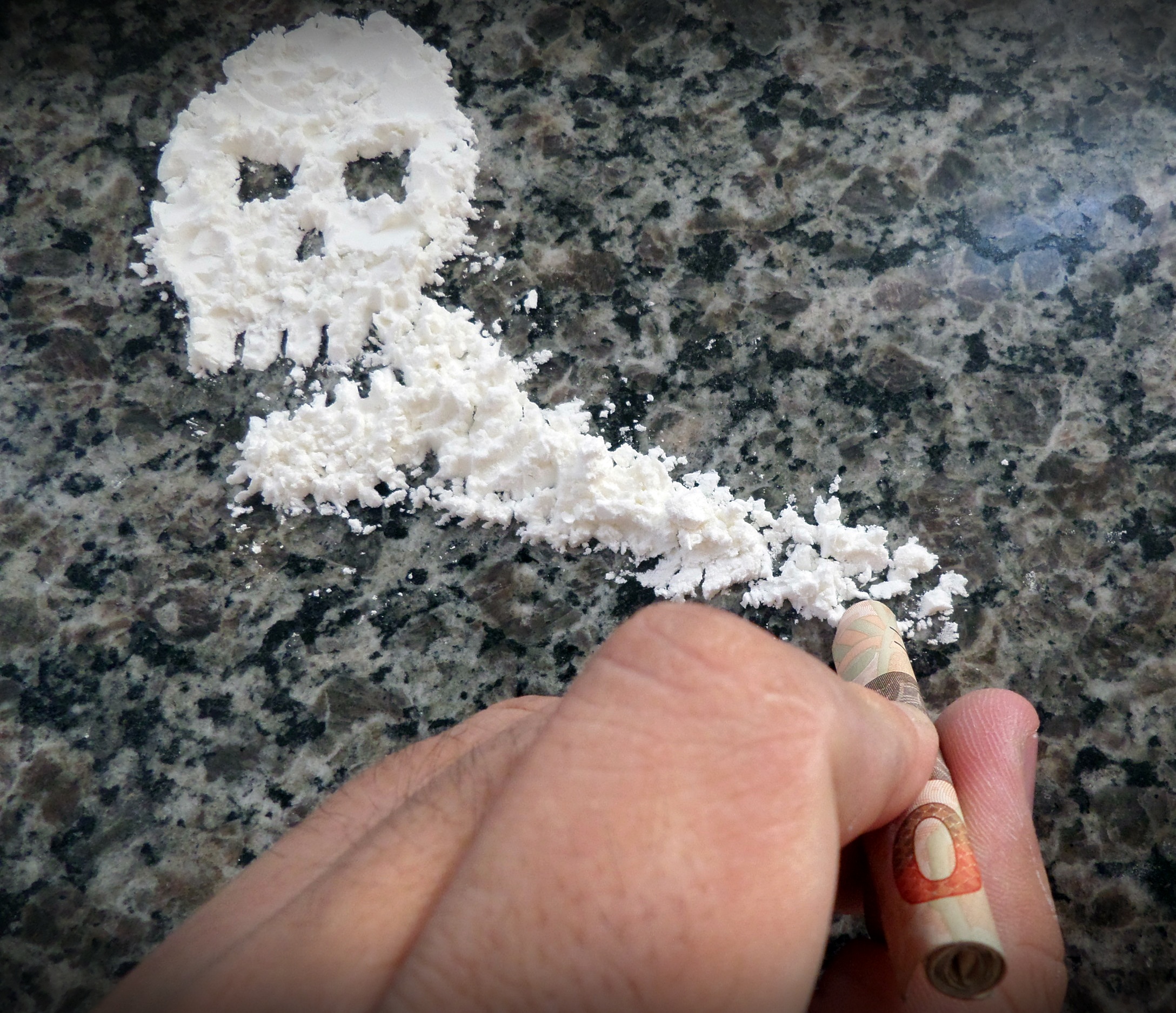

Image Source: Kuroaya

The study used two special breeds of rats: one breed was called the bred high responders (bHR) and the second breed was called the bred low responders (bLR). The bHR rats tend to explore and seek new or unfamiliar experiences, which makes them more prone to using and later abusing cocaine; whereas bLR rats tend to be anxious of such new experiences. These two rat breeds essentially allowed the scientists to study how the drug, specifically cocaine, affected gene expression and epigenetics in NAc. The rats were first trained to expect to find cocaine in specific places, poke their nose into those places to obtain a controlled dose of it, and expect cocaine to be available when a specific light was shining. The experiment observed that overtime, even the bLR mice learned to take the drug.

Here is where the experiment became dicey: even though both the rat breeds were trained similarly and given the same amount of cocaine dosage, their responses to seeking the drug varied dramatically. After one month without cocaine, bHR rats were more likely to start seeking cocaine again, relative to bLR rats, when shown the light stimulus that they were trained to associate with the cocaine. This pattern found in the rats closely relates to humans recovering from addictive substances: their craving for the drug returns when they view items associated with the drug. Overall, further research within this topic would help give understanding into how genetics play a role in abusing addictive substances and how these genetic markers within an individual’s DNA can be targeted to treat substance use disorders.

Feature Image Source: <ahref=”https://www.flickr.com/photos/imagensevangelicas/13957568572/in/photolist-ngobS1-5P7ExX-6TE1JC-nWD4tX-penm8-57ivi-GEh85-5TcPL3-2SJeB7-bxBMjA-bxBMjC-5TCeF2-kbNH9d-4MmCWw-9EMn8H-7fJY74-B7nf6a-6Mjm6g-96FGtV-4YHPqC-bs53en-JoXwhW-Bvgegz-C4M9mP-roCJtM-B7gC1q-6i4AMH-8kW8Mc-b4QCpX-4KubD5-4iiu-54Tqa8-4NyxWU-kxGSC-7PRNy6-678qPG-7uWQua-6ve44z-ngEwWF-cC6ag-591Uv-dohw5-7zSeWA-aWCqrB-7gYFh-i4ECpZ-bxBMj1-4tTesT-6ARYnU-3KxpnY” target=”_blank”>cocaine photo by Imagens Evangélicas