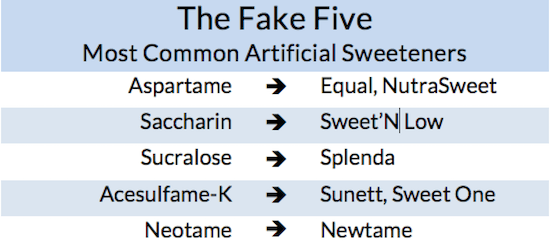

Artificial sweeteners have been getting a bad rap for over 40 years. The first study to cause widespread alarm, published in the 1970s, reported a link between consumption of saccharin (the artificial sweetener in Sweet’N Low) and bladder cancer in laboratory rats. Though it was later discovered that the process causing tumors in rats wasn’t even possible in humans, saccharin remained on the U.S. National Toxicology Program’s Report on Carcinogens until 2000.

Source: Taylor Henry

Aspartame, the compound in Equal and NutraSweet, has suffered even harsher accusations. In 1996, a study implied that the sweetener was to blame for the rising frequency of brain tumors in the 70s and 80s, despite the fact that this occurrence of brain cancer began to increase eight years before aspartame hit the market. Even more recently, researchers in 2005 reported that rats that were fed aspartame were more likely to develop lymphoma and leukemia. They failed to emphasize, however, that these results were significant for rats consuming extremely high doses of the sweetener—the human equivalent of drinking between eight and 2,000 diet sodas a day. Regardless of whether the findings mentioned above are relevant across species or can even be practically applied, scientific studies about artificial sweeteners have made a huge impact on the public’s perception of them.

Today, concerns about the safety of artificial sweeteners are a little less serious. Most researchers–and many consumers–are focused on the way calorie-free sweeteners influence weight gain and metabolic disease. Despite their popularity among dieters, a number of studies are finding that artificial sweeteners may actually increase weight over time, especially among children. How can a food with literally zero calories pack on the pounds? The most common hypothesis points to the way regular sugar impacts the brain. When we eat sugary foods, it activates the region of our brain associated with reward. This activation doesn’t happen when we eat sucralose, and it’s predicted that other artificial sweeteners fail to adequately fulfill our cravings as well.

The issue is thus not with artificial sweeteners themselves, but with the increased likelihood that people will continue eating to satisfy their sweet tooth, perhaps consuming more calories than if they had just eaten sugar in the first place. This may explain why artificial sweeteners have been more definitively linked to weight gain in children than in adults. Whereas an adult who drinks a diet soda may be consciously avoiding sugar, a child might eat until it feels satisfied, regardless of how many “sugar-free” snacks he or she has already had.

More concerning than body fat is the potential link between artificial sweeteners and glucose intolerance. A few small but fascinating studies have found that both rats and humans exhibit glucose intolerance after consuming saccharin, sucralose, or aspartame for a period of ten weeks. Because glucose intolerance indicates a pre-diabetic state, these findings may be bad news for those who consume artificial sweeteners on a regular basis.

As mentioned previously, artificial sweeteners have a history of being falsely accused. Although they may have a slight impact on weight, the most important thing for consumers to remember is to use both sugar and artificial sweeteners in moderation. While children should stay away from “sugar-free” products, the occasional diet soda won’t kill anybody.

Feature Image Source: Grid Engine