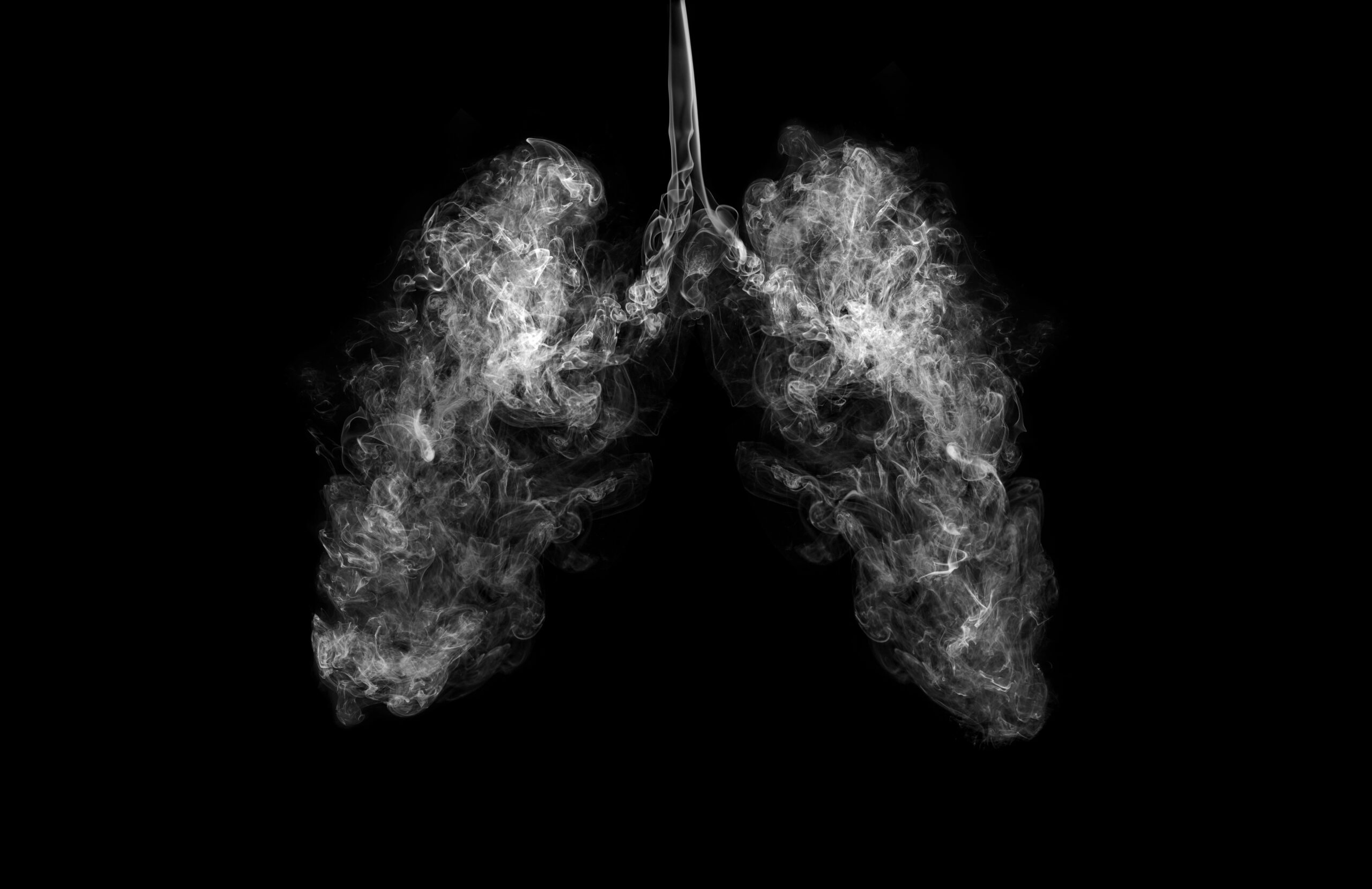

Pneumoconiosis, also known as “black lung,” has caused more than 76,000 deaths among miners from 1968 to 2014. The lung disease develops over prolonged exposure to coal dust, a common occurrence among miners. When the mining dust enters the lungs, it can remain trapped in the lungs and cause abrasions, usually detected on an X-ray or CT scan. The lung damage leads to increased rigidity of lung structures that interfere with breathing mechanisms and can cause a lack of oxygen. The process of lung scarring and stiffness develops after years of dust exposure. Possible early symptoms include trouble breathing, a heavy feeling in the chest, and coughing that may result in dark mucus. Other forms of pneumoconiosis can occur when individuals become exposed to different minerals such as sand, gravel, and silica. Considering the harmful effects of dust exposure, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration and Centers for Disease Control have discussed policies and regulations to limit exposure levels since the 1970s. However, with coal mining on the rise, cases of black lung disease continue to increase at dangerous rates.

Mine workers wear respiratory ventilation masks and protective equipment to reduce exposure to dust in the lungs. However, stricter regulations are necessary to minimize safety risks.

Image Source: CasarsaGuru

Recent reports about mining deaths due to pneumoconiosis highlight the need to update mining policies. One in five miners in the Appalachian have pneumoconiosis, with the average age of disease progression occurring at a younger age. Additionally, a 2010 incident at the Upper Big Branch mine in West Virginia reported 29 deaths among miners, with 17 individuals displaying black lung out of the 24 autopsies conducted. With a recent resurgence in mortality rates due to pneumoconiosis, the Mine Safety and Health Association sent a proposal in June stating that during an 8-hour work shift, the silica exposure limit should be altered to half its current regulated limit. This proposed rule cuts the maximum dust exposure limit from 100 to 50 micrograms per cubic meter of air. Although this would drastically improve conditions for workers, the reports on dust exposure levels come from mine operators, raising issues about falsified data that can continue to harm workers. To increase occupational safety, the National Mining Association is arguing for respiratory protection equipment to decrease dust exposure. However, unions supporting miners contend that the respiratory equipment provides inadequate ventilation. Thus, government officials need to be proactive in driving discussions and change to protect mine workers and compromise with mine operators.

Black lung cases among miners exemplify the strong correlation between health outcomes and environmental safety in places of work and residence. Ultimately, continuing interventions that increase safety and promote health can help eliminate the social determinants of health for mine workers.

Featured Image: lufeethebear